Penny Allen, born in Portland, Oregon, discovered theatre and created several shows in English and French before turning to cinema, where, still in Portland, she wrote, directed and produced two features, PROPERTY (prize winner in Sundance) and PAYDIRT. She then lived in Central Oregon for nine years before moving to Paris, where she first worked on environmental issues and published two books, one on the environment, METAPHORS FOR CHANGE, the other a memoir, A GEOGRAPHY OF SAINTS. She then returned to cinema with THE SOLDIER’S TALE, LATE FOR MY MOTHER’S FUNERAL (in French and Arabic), and THE DIDIER CONNECTION. She has lived in France for thirty years and is working on a new movie, called PUSHING PAST THE BAD. Her third book, the novel THIS RESCUE THING to be published in 2024, is based on real events in her life.

as director, author, producer, co-editor

PROPERTY

1978, fiction feature, 90 min, WNET television, USA, selected for US Film Festival (Sundance), prize winner, Northwest Film Festival, prize winner, Maverick Film Festival, New York, Rotterdam Film Festival, Florence Film Festival (Italy), Portuguese Film Festival, Hof Film Festival, Germany, Sydney Film Festival, Moscow Film Festival, Cineprobe, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Western States Arts Festival, prize winner, Gus Van Sant’s Carte Blanche at the Cinémathèque française, Paris, 2016, Casa Encindida, Madrid, 2018, La Rochelle Film Festival, 2019, Splendor Films, MARY-X Distribution (release in France, 2021), Canal Plus, 2021, London (The Barbican), Brussels, The Block Museum, Chicago, Museum of Modern Art, New York, with a streaming by MOMA, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Japan, 2023. Distribution Sundance VOD.

Rétrospectives: Metrograph, New York, 2017, Hollywood Cinema, Portland, 2016

Critics’ view

Screen Slate, by Madelyn Sutton, Jan., 2022

In the 1970s, activist, theater critic, and native Oregonian Penny Allen took part in a movement to rescue the Corbett-Terwilliger-Lair Hill neighborhood of Portland from high-rise developers. Inspired by this collective effort to maintain a beloved enclave of ramshackle Victorian homes and their eccentric tenants, Allen wrote a script that condensed the events and the broad swathe of people involved into what would become Property (1978), her feature film debut. Made with recent RISD graduate and first-time cinematographer Eric Alan Edwards (My Own Private Idaho, Cop Land), who brought college friend Gus Van Sant on board as sound recordist, the resulting film’s prescient, evergreen relevance and cast of indelible, intimately-captured characters make for an endlessly watchable if bittersweet time capsule.

Gentrification wasn’t yet the byword for what was happening in Allen’s hometown and thus doesn’t appear in the script. Yet much of what occurs will be painfully familiar to today’s viewers, who may find the film overly generous to its often self-centered, mostly white characters (in the words of one collectivist, “How many Black people live in this neighborhood, and why aren’t they here?”). The echoes of futility don’t end there: couch-surfing comedian Corky Hubbert (Legend) relates the excitement of demonstrations against the local Trojan Nuclear Power Plant, which was eventually shut down and demolished. Protests of that scope don’t seem to be coalescing today around this “safe” energy source, the expansion of which is encouraged by the Green New Deal.

Property’s lasting power doesn’t arise from its suggested alternatives to capitalist land grabs or any inspiring visions of success. Rather, the naturalistic performances from its charismatic cast—mostly local theatrical actors—bring humor and beauty to a decidedly depressing topic, and the roving, documentary-style 16mm camerawork imbues the film with tender immediacy. Lola Desmond and Marjorie (whose salaries were subsidized by the Federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) portray a part-time sex worker and a thrift-store upseller, respectively, and play their post-hippy antics with undeniable magnetism—just one aspect of Property that reappears in the films of Kelly Reichardt and Van Sant, to name a few of Allen’s Northwest indie successors.

Also : Cahiers du Cinéma, juillet-août, 2021, p. 50, « Property » de Penny Allen, La Quadrature du Cercle, by Eva Markovits

THE DIDIER CONNECTION

2013, 12 min, fiction/documentary, selected for the Northwest Filmmakers Festival, USA, International Festival of Women’s Films, Paris, Côté-Court, Paris, Kolkata Film Festival (prize winner), sold to Ciel Independant TV, CiCliq, France.

Critic’s view

Sheldon Renan, film critic

The Didier Connection is Allen’s shortest film but one that took 36 years to complete, so its apparent simplicity hides a surprising density. The Didier Connection is crisp, refreshing, optimistic, even seductive, like early Truffaut or Chris Marker. But submerged beneath the narrative momentum is a longing for life and time that can be experienced in memory but no longer truly touched. The visual look and feel is unique in my experience of short films and video – unique in showing the past as if it is still alive but visible only through the obscuring lens of decades of time.

LATE FOR MY MOTHER’S FUNERAL

selected for the Montreal World Film Festival, Maghreb des Films, Luxor Festival of African Films, Distributors, Independant Distribution, USA, Sundance VOD, Afrique Films.

Critic’s view

« Behind the Image » with Guy Ménard and Pierre Pageau, Radio Centre-Ville, Montreal, August 30, 2013, on the occasion of the Montreal World Film Festival

Late for My Mother’s Funeral plays magically with genres, capturing the viewer in its imaginary world. Very powerful, the film is a panorama about a family, a people, a contemporary human condition: A family without a country, a family caught in a web of nationalities while identifying with none of them. They aren’t really Algerian, or Moroccan, or French. Their identity lies in the grave with Zineb, their recently-deceased mother whom we are invited to imagine.

The film brings Zineb to life, this woman of great determination and force, capable of resolving any problem. Via an extraordinary intimacy we understand that Zineb was the source of identity for her ten stateless offspring, now adult. We watch them, behind closed doors, privy to their most intimate secrets, as they fabricate a new identity in Zineb’s absence.

The film is a fable of The Mother. I didn’t realize my mother’s importance when she was alive. Only when she died did I understand what I got from her. It’s tremendous when we are offered this knowledge through a film!

Organized around scenes developed through improvisation, the film portrays each of the offspring donning the mother’s dress (even the man) to evoke telling scenes, many of them touching on stories never told – the tensions between Algeria and Morocco, the private life of Islam, the marrying off of the youngest daughter Souaad, all of this told with the force of the real, all of it beautifully presented, with great freedom of form. It is a strong, impressive film, which takes the time to put everything in place, and thus we grasp that everything is part of a larger construct, one that brings us back to ourselves. Via this family, we rediscover ourselves.

THE SOLDIER’S TALE

(L’HISTOIRE DU SOLDAT)

2008, 54 min., creative documentary, selected for the festival Traces de Vie, Clermont-Ferrand, Kolkata (India) Film Festival, Documentary Fortnight, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Biennale du film d’action sociale, France, Festival of Womens’ Films, France, International Film Festival Nyon Visions du Réel (prize winner), Letters from the Times of War, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Distributors Baba Yaga Films, France, film released in Paris, Sundance VOD.

Critic’s view

Le Monde diplomatique – The Two Halves of America

by Mona Chollet

Américaine exilée à Paris, l’écrivaine Penny Allen se retrouve un jour, dans l’avion qui la ramène aux États-Unis, assise à côté d’un compatriote. C’est un soldat en uniforme. Il a une permission de deux semaines ; il était encore en Irak le matin même. La conversation s’engage ; ils découvrent qu’ils sont tous deux originaires du nord-ouest des États-Unis.

Le jeune homme, très agité, déverse sa colère : « Le jour, on distribue des bonbons aux gamins, et le soir, on revient pour tuer leur père. On est des bêtes ! Comment ces gens pourraient-ils nous aimer ? Qu’est-ce qu’on fout là ? On tue des gens. C’est ce qu’on fait ! Tu m’étonnes qu’ils nous haïssent ! Ces types mettent leur femme à l’arrière du camion, avec les moutons… On est des bêtes, tous ! » Il dit son tourment que lui, un chrétien, tue des gens.

Les deux voyageurs restent en contact, s’appellent, s’écrivent. Lors d’un autre séjour, Penny Allen persuade le sergent d’accepter un entretien filmé. Ils se rencontrent à mi-chemin entre leurs deux lieux de résidence, dans un motel – comme si « les deux moitiés de l’Amérique » se retrouvaient dans une chambre, dit-elle, car elle était opposée à l’invasion de l’Irak. Devant la caméra, le jeune homme apparaît presque hébété. Pour le moment, il travaille de nuit dans une usine. Il raconte que, lorsqu’il dit autour de lui qu’il rentre d’Irak, cela n’intéresse personne. Il s’attendait à un minimum de considération à l’égard de quelqu’un qui a risqué sa vie, et il ne rencontre que l’indifférence : « C’est comme si on rentrait de vacances. » Il faudrait rétablir la conscription, lance-t-il avec amertume. En dehors de cette femme rencontrée dans l’avion, il n’a personne avec qui parler de ce qu’il a vécu là-bas.

De fait, c’est un peu comme s’il voulait se conformer à l’idée selon laquelle il rentre de vacances. Il exhibe ses souvenirs : photos sur lesquelles les copains sourient largement – parfois aux côtés d’un prisonnier irakien, ce qui laisse deviner la hideuse banalité des clichés d’Abou Ghraib. Photos macabres de corps brûlés, mutilés, réduits en bouillie. Pourquoi les garde-t-il, ces photos ? Il ne le sait pas lui-même ; il explique que ce sont comme des vignettes (baseball cards) que l’on collectionne et que l’on échange avec les copains. En a-t-il besoin pour se persuader de la réalité de ce qu’il a vu et vécu ?

Il ne reste rien de la véhémence dont il faisait preuve dans l’avion. Peut-être à cause de la présence de la caméra ? Il s’efforce de souligner les « bons côtés » de ce qui, certains jours, admet-il, est bien « un enfer » : au moins, s’il repart, il pourra transmettre aux nouvelles recrues tous ces petits trucs qui permettent de survivre, et qui ne peuvent s’apprendre que d’expérience – laisser son arme dépasser par la vitre ouverte de son véhicule pour pouvoir répliquer plus rapidement à des tirs, par exemple. Il se raccroche au souvenir de deux petites filles brûlées qu’il a un jour sauvées, pour se persuader que sa mission là-bas est utile. Certes, il est hanté par le souvenir d’un enfant qu’il a tué accidentellement. Son cri du cœur de l’avion, « On est des bêtes, tous », s’est mué en une distinction plus classique entre « eux », qui sont des bêtes, et « nous », qui sommes des gens bien : les Irakiens s’entretuent, coupent la tête à leurs prisonniers, alors que les soldats américains, affirme-t-il, traitent toujours bien les leurs.

Contrairement à Penny Allen, le sergent n’a pas une « opinion » sur cette guerre. Il donne plutôt le sentiment de se rendre à toutes les raisons qui le poussent à accepter d’y retourner. La contrainte économique, d’abord : il a besoin de l’assurance médicale de l’armée pour son fils… Tout compte fait, dit-il, la guerre, « c’est un boulot super cool » – il finira de toute façon par perdre son emploi à l’usine. Il y a l’addiction à l’adrénaline, ensuite, et l’impossibilité de se réadapter à la vie civile : il ne s’anime un peu et ne retrouve son aisance que lorsqu’il parle de sa vie quotidienne en Irak : « Là-bas, au moins, personne ne vous cherche des noises. » L’esprit de corps, le patriotisme, font le reste : s’il désertait, ce serait « la honte » pour lui et sa famille. The Soldier’s Tale donne à voir comment toutes sortes de facteurs implacables se combinent pour faire taire une conscience, et pour rendre la révolte impossible – ou pour la réserver à une petite minorité.

PAYDIRT

1981, fiction feature 90 min., WNET television, USA, selected for US Film Festival (Sundance), Northwest Film Festival, Festival of American Independent Cinema, New York, Festival of American Independent Cinema, Netherlands, Hof Film Festival, Germany, American Films of the 80s, BAM, New York, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, Distributor Sundance VOD.

Critic’s view

The late 1960s and ‘70s saw a glorious boom of American regional filmmaking, and it was Franco-American Penny Allen who captured the particular eccentricities of the Pacific Northwest, then a last redoubt for the routed counterculture. Allen helped put Oregon on the map, long before Todd Haynes, Kelly Reichardt, and Gus Van Sant—who recorded sound on her breakthrough gentrification drama Property. In the years since she has continued to work in her own idiosyncratic, stubbornly independent manner, the influence of her films’ humanity and integrity enormous in Portland and beyond—and certain to grow after this vital retrospective. » – Metrograph

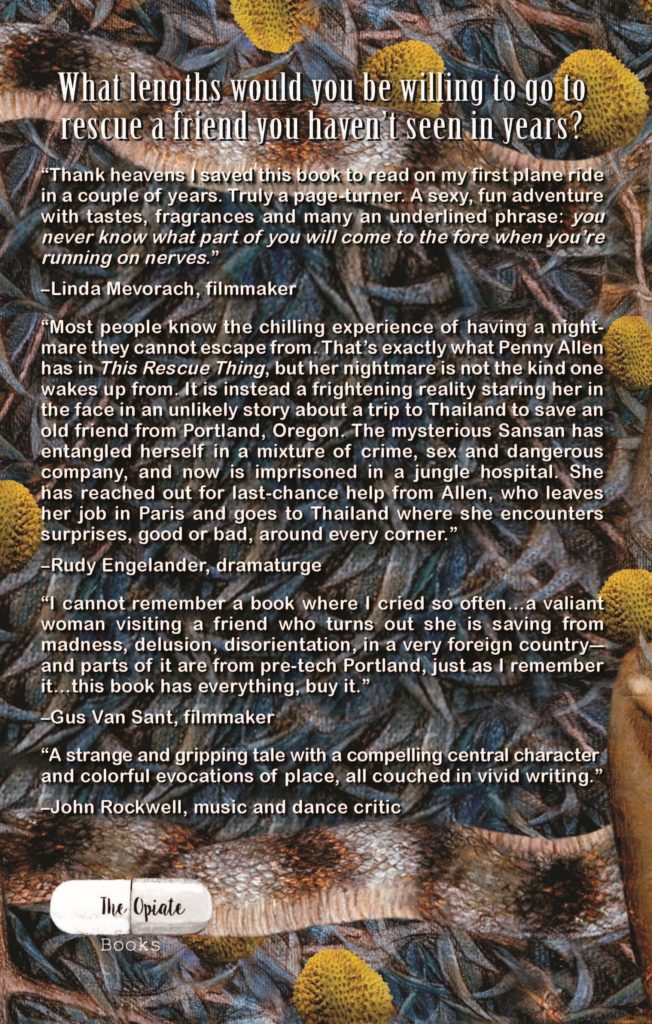

This Rescue Thing

Available April 2024

What lengths would you be willing to go to rescue a friend you haven’t seen in years? In Penny Allen’s staggering, often gut-punching novel, This Rescue Thing, the answer to that question unfolds in ways that delight, astonish and titillate. A feast for the senses, Allen’s evocative narrative takes us on a journey around the globe, from Portland to Paris to Bangkok, as the narrator finds her life irrevocably entangled with a force of nature named Sansan — the friend she chooses to rescue from a Thai mental facility after she contacts the narrator out of the blue to plea for help. Jumping face-first into the abyss to fulfill that request, the narrator embarks on the unexpected adventure of a lifetime, learning that some friendships are the kind that never die, no matter how long you go without seeing or talking to the person. Or how much their wild child personality might get you into trouble…